Padgett Powell ’74 is one of the most important figures in experimental fiction today. He’s a literary iconoclast par excellence, and the thread that binds his personal story is his refusal to obey convention and his unchanging attitude to challenge everything and everyone.

by Mark Berry

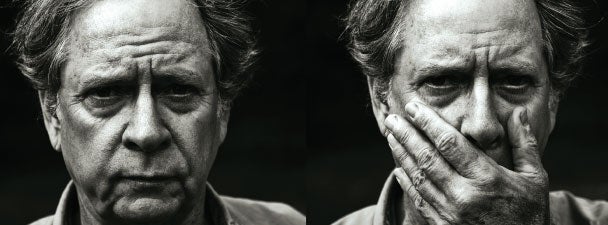

Photography by Ben Williams

“The cops have got Padgett,” Johnny Hamm yells from a third-story window of McClenaghan High School. Within seconds, dozens of boys serving afternoon detention with Hamm for various school violations (some in there for the excessive length of their sideburns) stream down the stairwell and out the door onto the school’s front lawn, where Padgett Powell is being put into the back of one of two squad cars for his distribution of a profane student magazine.

Within seconds, they surround the police car and begin shouting, “Pigs off campus! Pigs off campus!”

More students and bystanders descend on the scene, joining in the chant.

Pigs off campus! Pigs off campus!

The intensity of the moment is palpable. And for Powell, a senior at McClenaghan, it’s also sort of exhilarating – kind of like the energy you might feel at a Cream show or the benign ferocity on display at a bonfire pep rally during football season. It’s all fun, loud and a little dangerous – in a good way.

Pigs off campus! Pigs off campus!

But something changes. The adrenaline rush Powell feels subsides, replaced by a growing fear, like he’s stuck in the eye of a hurricane. Surrounded by the gathering mob, he can see that his classmates are getting more worked up, angrier. The police officer in Powell’s car radios the other squad car, “Grady, you want to pick up some more?”

Pigs off campus! Pigs off campus!

This is turning out to be no ordinary arrest in Florence, S.C. But then again, this is no ordinary time. It’s May 1970, and the country – the entire country – seems spinning out of control. Only two weeks before, in an attempt to quell an anti-war protest, the National Guard had shot and killed four Kent State students, wounding another nine. The turbulence that defined the 1960s is spilling over in this first spring of the new decade.

Pigs off campus! Pigs off campus!

Powell tries to calm the storm as best he can, signaling to his friends and classmates to bring the emotional level down. Miraculously, his hand gestures seem to work, tempers appear to dampen – at least momentarily – and the officers haul Powell and a friend to the local police station for the publication of an “underground underground magazine,” as Powell describes it.

Powell had been a guest columnist for The Free Press, the school’s “official” underground student newspaper. In it, students vented their frustrations on topics both local and global. They took issue with McClenaghan High’s annual fundraising drive of selling magazine subscriptions, they criticized the ongoing conflict in Vietnam and ran Mark Twain’s poem “The War Prayer” and lyrics from Bob Dylan’s “With God on Our Side” (one of his classic protest songs from 1964).

But for Powell, that wasn’t enough.

“I was mad,” he remembers. “I wanted The Free Press to be more revolutionary, so I figured I would produce my own thing. I wanted to express discontent … punch holes in the status quo. And I wanted it to be salacious and angry.”

Working in the basement of a local church, Powell used a borrowed mimeograph machine to print on three sheets of legal-size paper, creating his “salacious and angry” Tough Shit, a magazine of naked name, dated May 15, 1970.

In it, he took to task his own “Heavenly Class of Seventy” on their class night and their choice of class gift: a trophy case, purchased with funds raised by the much-maligned magazine subscription campaign. He writes: “All in all, a good night, ending with smiling, happy faces filing out, cattlelike … with the [s]ame contentment of cows listening to the tinkle of their bells.”

In general, the tone throughout the articles is confrontational and sarcastic, a protest against authority – principals, guidance counselors, teachers, “pet” students – anyone who is The Man, or in collusion with Him. And Powell’s argument, for so many teenagers on the cusp of adulthood, is timeless: Wake up, you bovines!

Most likely, a school administrator phoned the police after reading TS’s incendiary contents – offended, surely, by being the butt of so many jokes. But the language – the four-letter words and use of “cosmic orgasm” – perhaps proved the tipping point. You can just imagine the teachers and office staff peering through their window blinds out at this kid selling these stapled pages for a quarter in the school’s parking lot, and some must have thought, How dare this young man write such awful things!

When the police arrive, they find Powell selling TS out of the back of his Jeep. His unexpected arrest suddenly lands him in the company of some other literary giants, the likes of Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence, who had also faced their own obscenity charges.

After several hours waiting on a bench inside the police station, Powell and Jot Thames (the friend who was sitting in the Jeep waiting for a ride home) are escorted, along with Thames’ mother, who had arrived at the station, before the Florence chief of police.

“Mizz Thames,” Police Chief Adams says, “I can no longer address your son as a gentleman.”

Powell interrupts, “Chief, before you go any further, I want to say that Jot Thames here had nothing to do with this.”

Chief Adams, annoyed, turns away from Powell: “As I was saying, Mizz Thames, I can no longer address your son as a gentleman. …”

The die is cast. Or, at least, so it seems.

Two weeks later, Florence city prosecutor T. Kenneth Summerford summons the students involved and their parents to his chambers. Summerford, who five years later would capture national headlines with his prosecution of serial killer Pee Wee Gaskins, speaks to the parents on hand, an air of self-righteousness in his courtroom voice as he tells them that he’s not going to prosecute this easily winnable case since the students were “heretofore upstanding parties,” as Powell remembers. No, he isn’t going to shame these young men and women. He’s going to be generous and drop the charges. Expecting relief and appreciation on the faces of the parents, Summerford asks rhetorically, “Are there any questions?”

“Yeah,” says Mr. Thames, “I want to know why I had to get off work to come down here.”

“Padgett told Chief Adams that Jot had nothing to do with this,” Mrs. Thames adds, “and he ignored him.”

And with that, another small riot erupts on Powell’s behalf.

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Padgett?

What would you do? There he sits in your classroom. You know he’s listening, thinking, considering, analyzing, judging. Those ice-cold blue eyes staring a hole into you. God, he’s bright. Too bright, almost. But why does he challenge me on everything? How can I harness all that energy? This kid is going to be something some day. Good or bad, he’s going to be something.

Most likely, these questions plagued many of Powell’s teachers as he progressed from grade to grade. Certainly, Paul Skoko ’65, an English teacher at McClenaghan High, knew the difficulties that came with teaching Padgett Powell. During Powell’s senior year of 1969–70, Skoko was still young and enthusiastic and was the kind of teacher that would go on to influence generations of Florence teenagers on the beauty of literature and language. For many students, Mr. Skoko would be that one teacher that changed their lives for the better. He made connections, and he made one with Powell.

But a connection with Powell did not go without some sparks. Simply put, Powell liked to spar. He loved a good argument, a battle of wills. And like a boxer, he saw that kind of head-to-head conflict as honorable – and as necessary in the improvement of both fighters. His senior year, he brought the intellectual fight to Skoko in some unusual places.

For example, like most English teachers, Skoko required his students to write monthly book reviews. You know the drill: Read a book off the assigned reading list and write about its contents, its plot twists, character development, the author’s intentions, etc. Sounds reasonable. Well, Powell disagreed.

For one of these assignments, he turned in “The Psychology of the Book Review,” in which he argues that the book reviewer is a “despicable creature.”

In his preface note to Skoko, Powell explains his reasoning: “So I might claim honestly that my aversion for the Book Review is based simply on the belief that someday [sic] I will write a book, possibly just one, and the book reviewers, who have properly been called shits, will shit on it; they will kill it. The man writes books; the eunuch reviews them. So, to write reviews, even in fun, is to propagate a profession that someday [sic], I am sure, will chew me up and spit me out, cussing.”

Instead, Powell suggests that a book reviewer not read the work, but rather judge the piece on a “most stringent sensory evaluation,” meaning “look at its cover, design, type, page edge (smooth or serate); smell it inside and out (very important); listen to the pages flap, drop it on both hard and soft substances; taste cover and random pages; feel the texture of the paper used; and he should even test its ESP by quietly meditating while awaiting a message from the book.”

Remember, this is a 17-year-old kid writing a class assignment (or what he called his “anti-book reviews”). After 11 pages of advice and criticism, Powell ends his polemic against reviewers with this: “Knowledge is anathema: intuition is Truth, Beauty, corn, and a little scrambled eggs with ketchup. Get out and sniff a book!”

Perhaps Powell’s ultimate act of academic defiance was his high school senior paper, “undone,” in which he breezily answers the question on the similarities between the heroines of Gone With the Wind and Vanity Fair, of which, he earned a C-. But Powell tacked on another essay, covering the “condition of my mind.” In it, he expresses his disdain for the common, his notion of being a loser and the idea of suicides as “poor (or lucky) souls.”

For Skoko, it was too much. Powell’s essay(s) deserved a response – a heartfelt one that might also challenge Powell’s intellectual sensibilities as well as admonish him: “Padg, you can; do.”

He then addressed this insatiable student who had continually questioned his reading lists, the choice of “classics” and his assignments in general: “The world is full of things to be learned, facts (important and unimportant, magnitudinous and trivial), opinions, ideas, experiences, observations, etc. The true learner learns from everything. And he revels in learning. In a book he learns and revels. In an assigned book he learns and revels. In a budding bloom he learns and revels. In a crushed leaf he learns and revels. In a dog-eared page he learns and revels. In an ink spot he learns and revels. In an outdated educational system he learns and revels. In a raised eyebrow he learns and revels. In a tear he learns and revels. In an unspoken word he learns and revels. In all – ALL – he learns and revels. And though things are not what he would have them be, he learns and revels.”

But Skoko’s main point was this: “Don’t ignore the world.

Don’t not become involved. But don’t limit yourself in frustration. Go beyond.”

That was April, and in May, Powell was detained by the Florence Police Department in his literary efforts to go beyond.

The Reckoning

Although the obscenity charges were dropped against Powell for producing TS, there was a ripple effect beyond Florence, reaching all the way to the College, where Powell expected to enroll that upcoming fall on an academic scholarship.

Powell received a letter that he was to report to campus in June to explain this episode to the administration, and that his future at the College was on the line. Apparently, someone at McClenaghan High had contacted Willard Silcox ’33, the vice president of alumni affairs, about the arrest and thought Powell’s matriculation at the College a grave mistake.

His parents, as could be expected, were none too pleased and told Powell that he created this mess, he would now have to face the consequences on his own. Powell, who had moved to Florida with his parents after his high school graduation, took a train from Jacksonville and then hitchhiked downtown, where he stayed overnight at the YMCA.

The next morning, he went to campus and met with four men whom he thought looked like senators: Fred Daniels, director of admissions; Dean Womble, academic dean of the College; and biology professors Harry Freeman ’43 and Norman Chamberlain.

They talked, and Powell felt pretty confident: “They weren’t giggling, but there was definitely a level of snickering just underneath the surface.”

When Powell asked if and when these august figures would make a decision, they told him to walk around campus and come back in 20 minutes. Powell went to the Cistern Yard and sat down on a bench. His father, wearing a suit, materialized out of nowhere, it seemed.

“We probably had three or four talks in my life, and this was one of them,” Powell recalls of that conversation in front of Randolph Hall. “He told me that if I didn’t get in, it was not the end of the world. That was always his advice to me – that whatever happened, it was not the end of the world.”

When Powell returned to the office, the judgment was succinct: You’re in.

Walking the Talk

Once on campus, Powell took Mr. Skoko’s advice to heart: He learned and reveled. But he also rebelled, in his way.

He joined a fraternity. No rebellion in that, but the Kappa Sigmas were not your typical frat-boy group. On campus, Pi Kappa Phi and ATO were the two most prominent fraternities, while the Kappa Sigmas, started in 1970, were an assortment of others – guys like Powell who thought and acted differently. That is, until the Kappa Sigmas started getting more selective with their membership. And with that, Powell quit. His attraction to the group was predicated on their acceptance of those classic outsiders. For Powell, exclusivity was a joke, and now, he found the punch line no

longer funny.

In the classroom, his independent streak was rewarded, even cultivated by some of the faculty. One such professor was Nan Morrison.

She saw something special in his writing and his understanding of literature. “Padgett wrote this essay about a John Donne poem,” Morrison recalls. “The thesis was so ridiculous, something about how Donne’s poem anticipated Newton’s optics – but his insight into the poem … I learned something new about it. He was not afraid to come up with this way-out analysis. He would always

push himself.”

In Morrison’s Shakespeare class, Powell always sat in the back of the room. His answers, as classmate Harlan Greene ’74 remembers, seemed like one non sequitur followed by another. “It was hard to have normal conversations with him,” Greene laughs. “He was just drunk on the elixir of words. Padgett never called a spade a spade. He would call it something else.”

Why use only five words when you can use 20 seemed to be Powell’s raison d’être. Morrison agrees, smiling: “It’s impossible for Padgett to not say something with flair.”

His flair, however, could both unite and divide. As James Pritchard ’73 explains, “Padgett liked to set up situations and then step back and watch” – the equivalent of throwing a verbal hand grenade into the room and seeing how everyone responded to The Situation, as he might say.

“What I remember most,” says Pritchard, Powell’s roommate at 41 Bennett Street, “was that he had a really great sense of humor. We would always be laughing, tears in our eyes, at the expense of our fellow students.”

Like the yellow Chevy Nova that he drove, Powell just stood out. “There was an aura about him,” Anna Hohnadel ’76 says. “He didn’t do bad things. He was honest in a time when a lot of us were not prepared for that honesty. He was a character, with a capital C.”

But not all appreciated his Character.

Despite his editorial baggage from high school, Powell assumed the editor’s role of The Meteor, the student newspaper. President Ted Stern had a brief conversation with Powell, who was not the first choice, and Stern did not really mask his commands in his single question: “We are not going to have any problems, are we?”

But in true Powell fashion, The Meteor did not follow the journalistic tradition of straightforward reportage. According to Blaise Heltai ’76, “One year, Padgett wrote the entire Meteor – he wrote every word, including the editorials, the sports, the Greeks and the news. At one point, Padgett committed a prank theft, and then wrote about it, including potential suspects.”

For Donna Florio ’74, his editorial antics were not that amusing: “Some of my friends and I disliked the way he’d taken over the newspaper, coming up with a new zany name each month, the most memorable being The Fig Island Exponent. His stories usually had a decidedly non-journalistic bent – his sardonic personality came through loud and clear. (As a writer now myself, I’d likely call it ‘voice.’) But in 1973, we just didn’t get it. I went on something of an underground campaign against him, writing some letters to the editor under the pen name Mighty Ms. Padgett, of course, excoriated me in his rebuttals, but I was gratified by the knowledge that I’d put a burr under his saddle. After reading Edisto [Powell’s first novel], I felt a little bad about giving him such a hard time. It dawned on me then that he was seriously talented and that maybe I’d been too unimaginative to realize it.”

So, of course, this literary all-star majored in English, right?

No, even his choice of majors was a statement of defiance. In Bill Bradford’s English class, Powell butted heads, again challenging the assignments, even lampooning the literary critiques he was to write. Whereas Morrison cultivated that rebellious streak, Bradford, known for his seriousness and toughness, tried to suppress it. Powell’s paper: D, no comments, no red marks.

“I was an ambitious boy,” Powell laughs now. “I didn’t want to sit in the back seat of literature. I wanted to be in the driver’s seat.”

Powell’s response to the D was immediate. He marched over to Professor Gerald Gibson’s office, found out how many credit hours he needed to graduate and changed his major to chemistry.

A Literary Evolution

Here’s the story: Boy loves writing. Even after boy graduates college, boy continues to write – long letters to friends, family and former professors. Boy uses letter writing to fine-tune his craft and test out ideas and episodes that he will incorporate into his first novel. After years of working odd jobs, boy gets into an M.F.A. program in Houston and boy meets a writer who will change his life.

That writer is Don Barthelme, a postmodern experimental man of letters who came to the University of Houston in 1981. Upon his much-heralded arrival, Powell checked out some of his books from the library. “I couldn’t read them,” he admits. “I had never seen anything like this. I didn’t know what it meant.”

For Powell, fiction was Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Tennessee Williams, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and Gore Vidal. “You know, realism,” he explains, “self-aggrandizing realism, some of it – though it was pretty much middle of the road, tenable utterance about things. It wasn’t abstract painting.

“I was 30 years old,” he continues, “and it had not occurred to me that there could be some kind of writing that wasn’t realism, and the force of seeing that, of being that innocent, that stupid, kind of shook me up, and I think it made the notion of going in that direction attractive.”

As Barthelme read Powell’s fiction writing, which would become his debut novel, he was impressed with Powell’s lyrical style, although he told him, “Regrettably, I found you fully formed.”

“He thought he had,” Powell says. “And I thought so, too. But he had only seen Edisto, which was a realistic book with a preposterous center. The Huck Finn trick – you can make some impossible utterance and say it as a child, and we like that.”

And we did like that. His precocious 12-year-old Simons Everson Manigault, raised only on classic literature by an alcoholic English professor mother on a remote barrier island, struck a chord with the reading public. A selection of Edisto appeared in The New Yorker in November 1983, and the novel was a finalist for the National Book Award the following year.

Acclaim was being showered on the up-and-coming writer. Walker Percy, a stalwart of Southern fiction, said Powell’s novel was better than Catcher in the Rye. Nobel Laureate Saul Bellow considered Powell one of the best writers of his generation. He soon received the Prix de Rome of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Whiting Writer’s Award.

What do you do for an encore? Well, when you’re a rebel, you throw convention aside. You burn the bridge behind you and warm your hands on the flames, stoking the fires with an imagination gone wild.

“What I have written since Edisto has been a steady progression away from the realism that I was doing when Barthelme found me,” Powell says. “I progressed.”

Into the Abstract

Today, Powell is the co-director of the M.F.A. program in creative writing at the University of Florida, where he has been teaching since 1984. But don’t think smoking pipe and tweed jacket with well-worn elbow patches. Instead, imagine ripped shorts, boat shoes without socks and shirts better suited for carrying fishing tackle than fountain pens. His students affectionately describe him as looking like a psychotic game warden with intense hair, intense eyes, intense everything.

Powell, the father of two grown daughters, lives on the outskirts of Gainesville in a Victorian house set, as if by magic or by some Faulknerian plot twist, in the middle of dense Southern jungle with his pit bull, Schuping, and a brood of chickens. The only clue to his profession: the thousands of books, magazines and papers that line his floor-to-ceiling shelves throughout the house.

His literary works, as he predicted back in high school, have left some critics mystified, even angry in tone, although all of them praise his stylistic inventiveness, his ear for dialogue and his “wizardly prose,” as critic Robert Kelly wrote in The New York Times.

“You have to give yourself over to Padgett’s work,” observes novelist Kevin Wilson, a former student of Powell’s at Florida. “If you can, it’s worthwhile. People who read his work, they are fanatical – he inspires devotion.”

“He’s definitely a writer’s writer,” agrees Christopher Bachelder, another one of Powell’s M.F.A. progeny. “He pushes taboos, pushes subject matter. He’s not out to endear himself – he wants to rile things up. If the average reader is interested in the possibility of a sentence, of language getting mixed up in interesting ways, then Padgett is your writer.”

His latest work, The Interrogative Mood: A Novel?, certainly pushes and riles things up. This “novel” is written completely in questions. Matt Weiland, the book’s editor at Ecco Press, compares Powell to a tightrope walker: “In the hands of a lesser writer, this book could easily fail. Worse, it could have been boring, but Padgett stays on that high wire through the whole way and it becomes natural for the reader.”

The book garnered a lot of attention: glowing praise from The New York Times as well as a Sunday magazine story, rave reviews from around the country, NPR coverage and – most important – buzz about his literary daring.

“The Interrogative Mood has touched people in this very direct way,” says Weiland, who also mentions that the book already has six foreign editions and was a bestseller in the U.K. “People are moved by it, and some are even trying to answer every question that the book poses.”

One such person is Anna-Bet Bester, a copywriter and blogger who impulsively bought The Interrogative Mood in a small bookshop in Hermanus, a vacation town on the south coast of South Africa. Her blog is dedicated to answering Powell’s questions, such as “could you lie down and take a rest on a sidewalk?” and “how do you stand in relation to the potato?” For her, the book “made for a reading experience so intrinsically weird that it made my brain do all kinds of wonderful things; somehow the barrage of questions ended up taking stagnant ideas, mashing it together and creating something brand new.”

And that is what Powell will be remembered for: creating something new, something different. His works are like jazz, rhythmic and unexpected. They also challenge us – much in the way he provoked and questioned the conventions of authority he faced from high school and beyond.

Perhaps the final observation on Powell’s writing should come from Nan Morrison – the English professor who encouraged his passionate resistance to the traditional; who served, as he says, as “my literary mother” and inspired moments in Edisto; and to whom he dedicated his novel Mrs. Hollingsworth’s Men.

“I want something from literature,” Morrison says. “I want something to take away with me. If I spend that much time reading something, I want to have seen something that I have never seen, feel something that I have never felt or know something that I have never known. You have that with Padgett. You definitely see something you’ve never seen before. And after reading anything by him, whether a short story or novel, even an email, you know he’s not satisfied unless he is doing something different.”